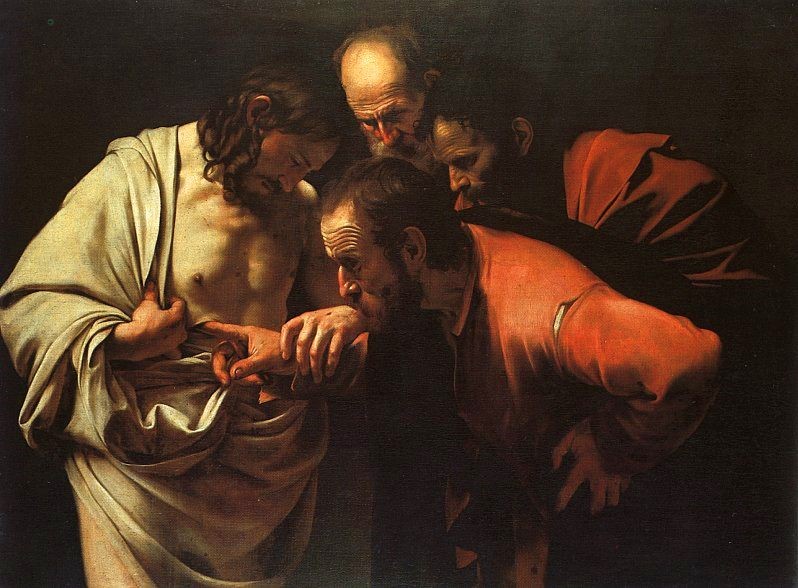

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 1601?, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Surely Jesus’s disciples knew what might happen. They’d been with Thomas through many difficult times and many joyful times, banded together, trailing behind Jesus for several years. They had plenty of time to learn Thomas’s quirks and oddities. So when Thomas said he just couldn’t believe it was true, they weren’t worried that Thomas had lost confidence in Christ. After all, even though Jesus had proclaimed that He was resurrection and life, it's still a difficult thing to believe. Perhaps Thomas had switched his loyalty, but no more than any of the other disciples when their boat was about to sink to the bottom of the sea, before Jesus calmed the waves. These disciples knew that Thomas's disbelief would be met once again by the capacious embrace of Jesus—they’d seen Jesus do that and more, many times.

As Caravaggio would have it, Thomas is a working man. His clothes are rough, and in an earthen hue. These are not fabrics made to impress others. Even as a working man, these clothes are probably not the finest Thomas has ever worn. The torn seam on his shoulder belies the clothing’s toughness, as well as the rough treatment of Thomas’s work. Or maybe Thomas was just too busy to stitch it back up. His fingernails are dirty.

More striking than Thomas's clothes are his eyes. Thomas does not look at Jesus’s wound. He looks outside the frame, and his eyes are unfocused. These are the eyes of a blind man. Jesus even grips Thomas’s wrist, guiding the hand to the wound. Dozens of other artists have depicted this scene, but none of them have given Thomas the wandering, unfocused eyes of a blind man. Guercino has Thomas looking squarely at the wound on Jesus’s side, his hand confidently stretching out to touch the wound, with no help from Jesus. Guercino’s Thomas is confident in the midst of doubt. Guercino's Thomas is a man who believes easily, so long as he is given physical evidence. This Thomas might doubt the resurrection, but he certainly believes his sense of touch and sight. On the other extreme, the French painter F.J. Navez has Thomas's hand reaching out to a bloodless wound on Christ's side, while Thomas himself stands in a rapturous, spiritual pose, his hand not quite reaching the wound. The doubting disciple is in a trance. Navez's Thomas only needs an emotional, spiritual experience to believe in the miracle of the resurrection. There is no blood, no real reason Thomas would even need to touch the wound. Navez’s painting belies a theology which really doesn’t need the body.

Contrasting with both Guercino and Navez, Caravaggio's Thomas dwells in both body and spirit. This Thomas is a practical man-of-the-world, innocent in his blindness. He does not rely naively on physical evidence, nor is he easily swayed by spiritual emotions. The moment we arrive on the scene, Thomas's dirty finger has already found its way underneath Jesus’s skin, but it is before Thomas has settled his eyes and his mind. The truth of the resurrection hangs in the air, unacknowledged, but nevertheless real. It is before Jesus says “blessed are those who did not see and yet still believe.”

I think Caravaggio knew that Jesus’s words were not meant to condemn Thomas, but rather to show us all who we really are before our eyes and heart match—before we see Jesus for who He is. Thomas poses humbly in his workman's clothes, turned toward Christ but not yet persuaded. Thomas here has not asked Christ to overcome some outrageous intellectual standard. But at the same time, Thomas wants whatever he believes in his heart to also make sense in his mind. If that is what it means to doubt, then so be it. The other disciples have their own path to Christ. It seems to me that Caravaggio knew the difference between disbelief and belief, between distraction and attention, between self-focus and love, between condemnation and the warm embrace of Christ.

Jeremy Knapp